The Geometry of Reverence: Kumihimo and Shinto Cosmology

The scent of aged wood, the whisper of silk, the slow, meditative rhythm of the braiding – these are the sensory anchors that pull me back to the world of Kumihimo. It’s more than a craft; it’s a tangible link to centuries of Japanese history, a quiet conversation with artisans long passed. I remember, as a child, discovering a small, intricately braided pouch tucked away in my grandmother’s attic. Its purpose, lost to time, remained an enigma, but the sheer beauty of the braiding captivated me. It felt imbued with a presence, a silent story waiting to be understood. It sparked a lifelong fascination with this remarkable technique, and increasingly, a desire to understand its deeper roots.

Kumihimo, meaning “gathered threads,” is a traditional Japanese braiding technique used to create cords, often used for kimono belts (obi) and samurai armor. The earliest documented examples trace back to the Kofun period (c. 300-538 CE), though oral traditions suggest its origins are even older, possibly reaching back to the Yayoi period (300 BCE – 300 CE). Initially, these braids were simple, functional, serving a practical purpose. Over time, however, they evolved into objects of exquisite beauty, demanding incredible skill and patience. The transformation from basic cord to intricate braid is a testament to the Japanese appreciation for refinement and understated elegance – qualities deeply intertwined with Shinto beliefs.

The Spiral and the Kami: Echoes of Shinto Cosmology

Shinto, or *Shin-no-Ken*, “the Way of the Gods,” is the indigenous religion of Japan. It’s a deeply animistic faith, believing that *kami* (spirits) reside in all things – mountains, trees, rivers, even rocks. This belief fosters a profound sense of interconnectedness and reverence for the natural world. And it's here that the geometry of Kumihimo begins to resonate with deeper meaning. Many traditional Kumihimo patterns, particularly those used in the creation of obi, exhibit striking geometric forms – circles, spirals, and repeated motifs.

Consider the spiral. In Shinto, the spiral is a powerful symbol representing the eternal cycle of life, death, and rebirth, mirroring the movement of the sun, moon, and stars. The swirling patterns in some Kumihimo braids visually embody this cyclical nature, reflecting the constant flow of energy and the interconnectedness of all things. The act of braiding itself can be seen as a meditative practice, a way to embody this cyclical flow and connect with the *kami*.

Circles, too, hold significant importance. They symbolize harmony, wholeness, and the universe itself. The circular designs found in Kumihimo, often incorporating repeating patterns, evoke a sense of balance and unity – core tenets of Shinto philosophy. The repeated motifs are not merely decorative; they are visual prayers, affirmations of the interconnectedness of all beings.

Beyond Function: The Craftsmanship of Reverence

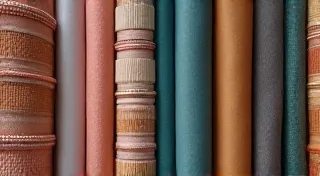

The level of craftsmanship involved in creating traditional Kumihimo is staggering. The finest braids were (and are) created from the highest quality silk, often dyed with natural pigments derived from plants and minerals. The process demanded absolute precision and unwavering concentration. Mistakes were not tolerated, and a single flaw could render the entire braid unusable. The artisans, often highly respected members of their communities, weren’t just crafting cords; they were creating works of art, imbuing them with their skill, dedication, and a profound sense of reverence.

I recently had the opportunity to speak with a master Kumihimo artisan, Mr. Tanaka, in Kyoto. He explained that for him, the act of braiding is a form of meditation, a way to connect with his ancestors and to honor the traditions of his craft. "Each thread," he said, his voice gentle and deliberate, "holds a part of my spirit. I strive to create something that will endure, something that will be appreciated by future generations." His words underscored the deep spiritual connection that many artisans have with their work.

The Resilience of Tradition: Modern Interpretations and Preservation

Like many traditional crafts, Kumihimo faced challenges during periods of modernization and Western influence. However, thanks to the dedication of artisans and the growing appreciation for Japanese heritage, the technique has experienced a resurgence in recent years. While traditional applications remain vital – adorning ceremonial garments and restoring antique armor – modern artisans are exploring new and innovative uses for Kumihimo, incorporating it into fashion accessories, jewelry, and even contemporary art installations.

Preserving the knowledge and skills associated with Kumihimo is a crucial task. Several organizations and individuals are working tirelessly to document traditional techniques, to teach apprentices, and to ensure that this remarkable craft continues to thrive. The existence of antique braiding stands (*Tategami*) is increasingly rare, but their preservation and restoration are vital to the transmission of the knowledge they represent.

The care and restoration of these antique stands requires not only technical skill but also a deep respect for their historical significance. Understanding the mechanics of these intricate devices, often complex arrangements of spools and levers, allows us to appreciate the ingenuity of the artisans who created them. The faint scent of old wood and oil clinging to these stands is a palpable link to the past, a reminder of the generations of artisans who dedicated their lives to perfecting this art.

A Thread to the Past, a Vision for the Future

The history and craft of Kumihimo are more than just a story of intricate braids and skillful hands; it's a window into the soul of Japan, a tangible expression of Shinto cosmology, and a testament to the enduring power of tradition. As I continue to explore this captivating art form, I find myself drawn not only to the beauty of the finished product but also to the profound sense of connection it evokes – a connection to the past, to the natural world, and to the enduring spirit of Japanese artistry. It's a journey of discovery, woven thread by thread, a quiet reverence for a geometry born of belief.